At the time of this writing, on the cusp of the year 2025, literacy is in peril at the most foundational level that it can be imperilled: access. This essay does not refer to the gaps of whole-language versus phonics-based ways of teaching literacy that showed in diminishing competency in schoolchildren continuing their education after the 2020 global pandemic. Rather, the focus of this essay is the mature and competent reader’s access to texts. Initiatives to severely limit access to literature are succeeding in a prominent chunk of the Anglosphere, and that is bad.

Book Bans in the United States of America, 2023 to 2024 CE

Elizabeth Blair reported in an article for the National Public Radio broadcasting website in April 2024, that the United States had “4,349 instances of book bans across 23 states and 52 public school districts” between July and December of 2023. In October of 2023, President of Scholastic Trade Publishing Ellie Berger released a statement concerning the accessibility of diverse publications at the publishing house’s book fairs. Love in the Library authored by Maggie Tokuda-Hall and illustrated by Yas Imamura is one example of a challenged book as it tells the true story of the author's grandparents meeting at the library of a Japanese-American internment camp (this publication was banned in April 2023. Another example is British author Alice Oseman's young adult graphic novel series Heartstopper that was no longer available to Young Adults at the Columbia-Marion County Public Library due to the depictions of young queer characters in romantic relationships to a degree expected and encouraged in heterosexual fictions (this publication was banned in August 2023.)

Stages of Desolation

In these early initiatives to hinder access to literature, adult authors may still write, publish, and earn from sales of their writings to adult readers. The publishing industry may continue this way for the foreseeable future.

We authors, readers, publishers, distributors, academics, citizens of the world must be wary of the progression of censorship: should the definition of “harmful content” from which children must be protected include mentioning the existence of racialized grandparents, or an ambiguously gay classmate, or any sort of person that censors think shouldn't exist and think that's possible to do in real life if we try hard enough to censor the fictions; should the production or dissemination of fiction constrained by its inanimate paper-and-ink form come to be treated the same as a physical assault from a living human criminal; and finally should this escalate from criminalized distribution turn into criminalized possession...we would all suffer from the state violence of search, seizure, and destruction of writings that are merely suspected of being verboten.

Why That's Bad and the Best Thing To Do About It

To quote American author Toni Morrison’s 2008 essay, titled Peril: “We all know nations that can be identified by the flight of writers from their shores. These are regimes whose fear of unmonitored writing is justified because truth is trouble. It is trouble for the warmonger, the torturer, the corporate thief, the political hack, the corrupt justice system, and for a comatose public. Unpersecuted, unjailed, unharassed writers are trouble for the ignorant bully, the sly racist, and the predators feeding off the world’s resources. The alarm, the disquiet, writers raise is instructive because it is open and vulnerable, because if unpoliced it is threatening. Therefore the historical suppression of writers is the earliest harbinger of the steady peeling away of additional rights and liberties that will follow.”

I still personally disagree with Morrison on one point: that censorship of art or fiction indicates quite that much more than the fragility of the people clambering to the top of a whole regime. Cultural norms are not, I think, as fragile themselves, but the attitudes surrounding them certainly betray an insufferably precious and fragile attitude in its adherents. No matter what the sentences say, the reader is responsible for thinking critically about what content from the book gets reified in the reader's real life. I just think the only direct, surefire way for literature to actively harm somebody is if another person bludgeons them with a hardbound. Book bans add the insult of absurdity to the injury of condescension.

The endeavor to preserve literature is futile if the people whose lives would be most enriched by these stories are unable to find them. When the literature created by living authors is targeted for segregation or censorship–because the authors or the stories represent the indigenous or the immigrant or the disabled or the queer or any combination or persons unmentioned–then early on in the stages described above, the best protection against censorship of those texts is the same as any lover of literature must do the whole time: support author lives and livelihoods. Purchase the books in such a way that the authors can directly benefit. Recommend and advertise these works, so that they reach readers.

On Chapbooks

The purchase of an ebook is not a purchase of an item that you now own: it is the purchase of a license to access that material on a platform, for as long as the platform itself deigns to host it. Cloud storage, for all its convenience, is similarly susceptible to missing data. Centralized institutions are more vulnerable to being targeted by the violence of government-policy censorship, as we may all remember of the legends of the third-century BCE Library of Alexandria and the ransacking of its remnant in the Serapeum of the same city. The failure to network distribution, the failure to document the shifts in available information, and the failure to duplicate texts are what can lose us these valuable stories forever. Digital or cloud access may be sustained for as long as possible, but a variety of the forms of the same text would be even better. The book as a physical item has some advantages that the same information stored digitally would be at risk for.

For as long as a civilization of mostly-literate people and the technology to support that literacy endures, written stories and information will have hope of survival. In this section, I aim to examine some of that technology:

Handwriting on paper. We've skipped past clay tablet and stylus or animal-skin palimpsests for something convenient to use and easy to obtain. Whether a notebook is a collection of inspirational quotes in chicken-scratch scrawl handwriting, or loose leaf for calligraphy practice, epistles to correspondents, or a grocery list, you are participating in literacy and rescuing civilization from decline.

Typewriters. We've skipped past letterpress printing with the movable type plate for something faster to create writing with than handwritten, generally more consistent and easier to read, less convenient in some other ways, and not impossible to obtain. Let's celebrate the typewriter for a moment, a distraction-free word processing tool, with its ink ribbons and sticky keys. Before computer processors and printers proved more efficient, some typewriters could be touted as travel-friendly, while other typewriter models with wider paper-carriages could type recto-verso without removing or realigning the paper. Parts for repairs have been increasingly difficult to come by, but with enough market demand that might change to more ready accessibility.

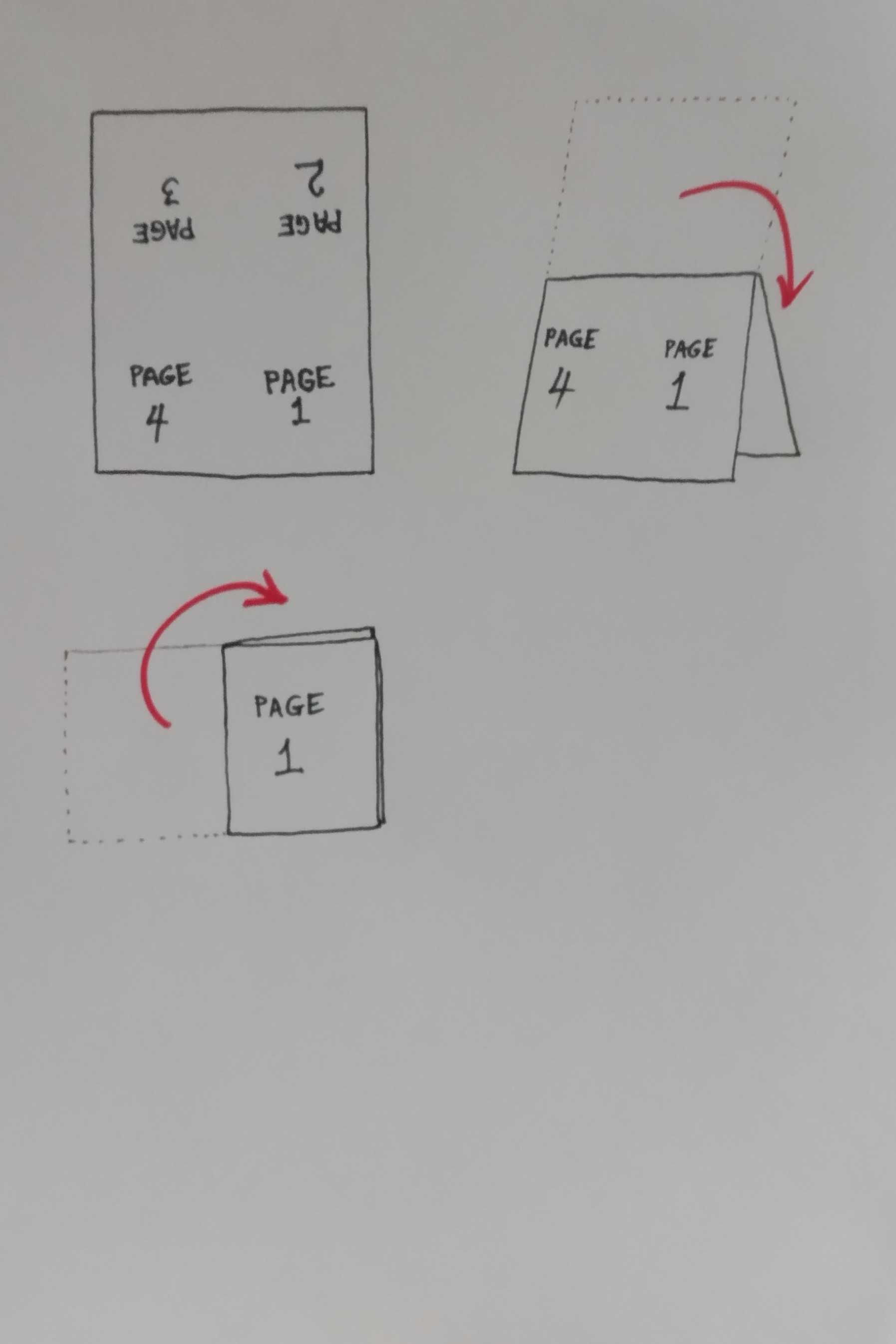

Xerox Machines, Printers and Scanners. Black ink on white paper would be the easiest to produce and reproduce. Consider a combination of xerox copies of a page and the quarter-fold style of chapbook for ephemera.

a portrait-orientation sheet of paper turns into

a pamphlet a quarter of its size by being folded in

half and half again, resulting in a booklet;

the above drawing shows the ideal orientation of

the text in the page and the page sequence

so that the resulting booklet

can be read easily in sequence

Anyone seeking to print their own chapbooks might be able to use one at a library or university printing/bookbinding shop, in the hands of somebody who knows by then what facing pages are. Some printers are capable of fullbleed printing or duplex, the latter of which would be a useful feature in multi-page chapbooks that use the booklet setting.

A note on thermal printers: Thermal printers require thermal paper that is only meant to last maybe 5 years because it fades or gets scratched off, and it's responsive to heat or chemicals that a spritz of rubbing alcohol will blot any words out. At the time of this writing in early 2025, this technology is not advisable to use for literature preservation.

On Bookbinding

Now that we have familiarity with getting ink words on paper and formating simple chapbooks, we can move on to bookbinding. The bone-folder tool pictured below can be used to press against the creases in paper to make crisp and sturdy folds. The bone-folder can be substituted with a sanded Sharpie marker or an expired bank card. When printers do not provide the fullbleed feature, then the blank spaces can be trimmed with a ruler guideline and razor (or a guillotine paper-cutter).

waxed thread, needles, an awl, & bone folder

A common format for comic books or graphic novels is that the sheets of paper 10.25-inches at the short side and at least 13.25 inches in length have the panels formatted recto-verso, then are folded and stapled with a long-arm or long-reach stapler to keep the page sequence in place. This is a good example of formatting "signatures" in thicker texts that are often sewn or glued together instead of stapled. I cannot write more about how to make a comic book zine or chapbook because I only discovered yesterday that screentone sticker-sheets existed. I still live in a time that speech bubbles were stuck there manually as in with paper, and it was somebody's job to remove the shadows cast by the extra paper layer of speech bubble. Censorship of comic books and graphic novels as literature do have a fascinating history, such as with establishing the Comics Code Authority that stymied the contributions of Bernard Krigstein (according to Matt Levin) and unfortunately have a fascinating present-time with the banning of Maus for the depiction of a nude mouse.

At this time, I also cannot provide instructions involving glue-binding, because I stick to thread-binding.